I’m turning Japanese

I think I’m turning Japanese

I really think so.

(Part of the lyrics of Turning Japanese by the Vapors)

Seiged by recent articles that describe how hundreds of thousands of Korean children were stolen from Korean parents in the 1970’s and 1980’s to be shipped to eager Europeans and Americans, I fear that the little I know about my origins—that I was left in a basket on the steps of the Norijangin police station in Seoul, South Korea with a birthdate pinned to me—-could be false. It’s upsetting to imagine that I could have been stolen when I’d always imagined a teen mother gently laying me and my basket on the steps of the station. Geez, grant me this one, poetic image!

It’s surprising that I never tried to find my birth family because I’ve seen the transformation that can happen to adoptees who find their birth families. One year at Carleton College, I had a particularly grim job in Student Services (our copy/collating center). My only college aged co-worker was a morose, chubby-faced Korean-American guy who dutifully did his homework during our considerable down time and rarely spoke to me, which I found unnerving. How I’d struggle not to doze off during my two hour shift—the hypnotic sound of the industrial sized collating machine in the background. I somehow found out my coworker was a Korean-American adoptee. (Though, I note that this discovered bond didn’t seem to warm him to me.) I quickly assessed him as depressed for he’d sit slumped in his chair next to me—unwilling to crack the slightest smile at my inane, desperate -to- fill -empty-space-chatter. In those endless hours, I’d notice the minutiae, he only wore gray socks folded over primly. His hair was downright curly so I wondered if he’d permed it. Once, I watched him take one pinky and absentmindedly scratch off the scars on his acne ridden face. But after one winter break, he returned—almost unrecognizable. He spun into the Copy room—his skin clear and his eyes lit—and explained he’d met his Korean birth mom. From that day on, he was positively verbose and ebullient. Quite a seismic shift!

Regardless, I’ve always been ambivalent about searching for my birth family. The pessimist in me imagines that if I met my family, they’d check me out, scoff and waive me away. (That is a scenario I couldn’t stomach.) But perhaps recent news of fraudulent adoptions and villainous adoption agencies, has left me hungry for more information about my origins. When my friend Lisa, an amateur geneologist with a curious mind and big heart who has helped friends and family locate their blood relatives, recently encouraged me to revisit my old Ancestry.com profile to see if we could locate any of my Korean relatives, I enthusiastically (but skeptically) watched her crack open my laptop. To my delight, I learned a fun fact: since the last time I checked my profile years ago, I am no longer 100% Korean; I am 6% Japanese and 94% Korean. As my friend explained, I probably had a Japanese great great grandparent or two half Japanese great great grandparents. Though I realize this may not be earth-shattering information for most, for me— an adoptee who knows so little about my birth family— it’s cause for celebration and wonder.

Of course, since learning of my Japanese lineage, the above lyrics from the 1980’s song Turning Japanese replay in my head. According to the songwriter David Fenton, “Turning Japanese is all the clichés about angst and youth and turning into something you didn’t expect.” Indeed, I didn’t expect to be part Japanese. Though now, looking back, I am thinking, well it makes perfect sense because I really do love Japanese food, anime, films, literature and all (but then again, so does so much of the world).

My friend and I (perhaps tastelessly) joked that I would suddenly wholesale adopt my newfound Japanese identity, e.g., say Arigato instead of thank you and greet her next time in a kimono and my face painted white—Kabuki style. I haven’t embarrassed myself that way yet but I do feel an elevated interest in Japanese culture and a renewed vigor about planning an eventual trip to Korea and Japan.

This has me thinking, what does it mean to be Japanese? I admit, I’ve gathered some stereotypes that I’d like to be disabused of, such as Japanese are often but not uniformly neat, orderly and polite. (I’ve got a similar stereotype of Germans, ridiculously gained from struggling with a suitcase in very quiet, elegant Berlin hotel lobby—my errant bag thrashing against a marble wall to the stern gaze of the staff). My other very, very anecdotal evidence about Japanese people comes from the time when I went to get my hair dyed at my Japanese hair salon that I regularly frequent and my hair stylist sat me in a fine cream-colored leather chair—my head fresh with black dye. Absent-minded me somehow touched my hair and a small black smear ended up on the chair arm. This caused a team of staff to surround my chair while I bled apologies and offered to pay for any cleaning necessary. They, clearly annoyed, silently scrubbed the chair with special solvent for what seemed like an eternity and politely waived away my apologies. But every time since, my hair dresser will with some ceremony spend an inordinate amount of time covering his chair with an excess of material, visibly annoyed as if reliving the memory. (I understand the annoyance but really why put anyone in a white leather custom made chair after dripping them with black hair dye? Duh! I somehow think I would have preferred if someone smacked me gently on the head and yelled “you dumb fuck!”)

Watching the riveting Season 1 and what has aired of Season 2 of Pachinko on Apple TV, I’m of course reminded of some bad history, that is Japan’s brutal colonialization of South Korea from 1910 to 1945 that was undeniably shameful and explains lingering tension between South Korea and Japan. I just learned that during the 2018 Olympic Winter Games, South Koreans demanded an apology from NBC after a commentator said that Korea’s transformation into a global powerhouse was due to the “cultural, technological and economic example” of Japan.

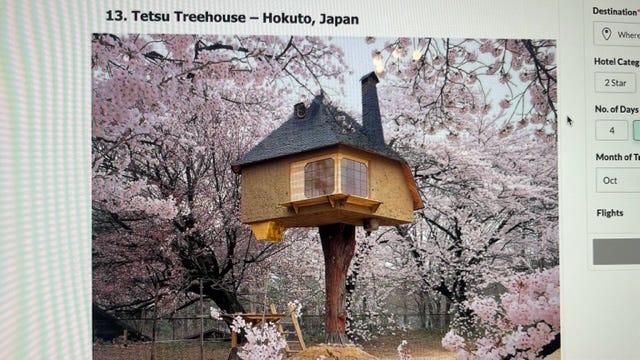

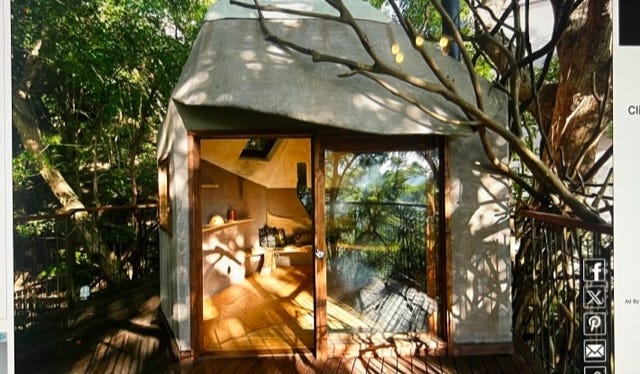

But certainly outweighing my negative associations with Japan, are voluminous positive ones. Take the art, the architecture, these treehouses below:

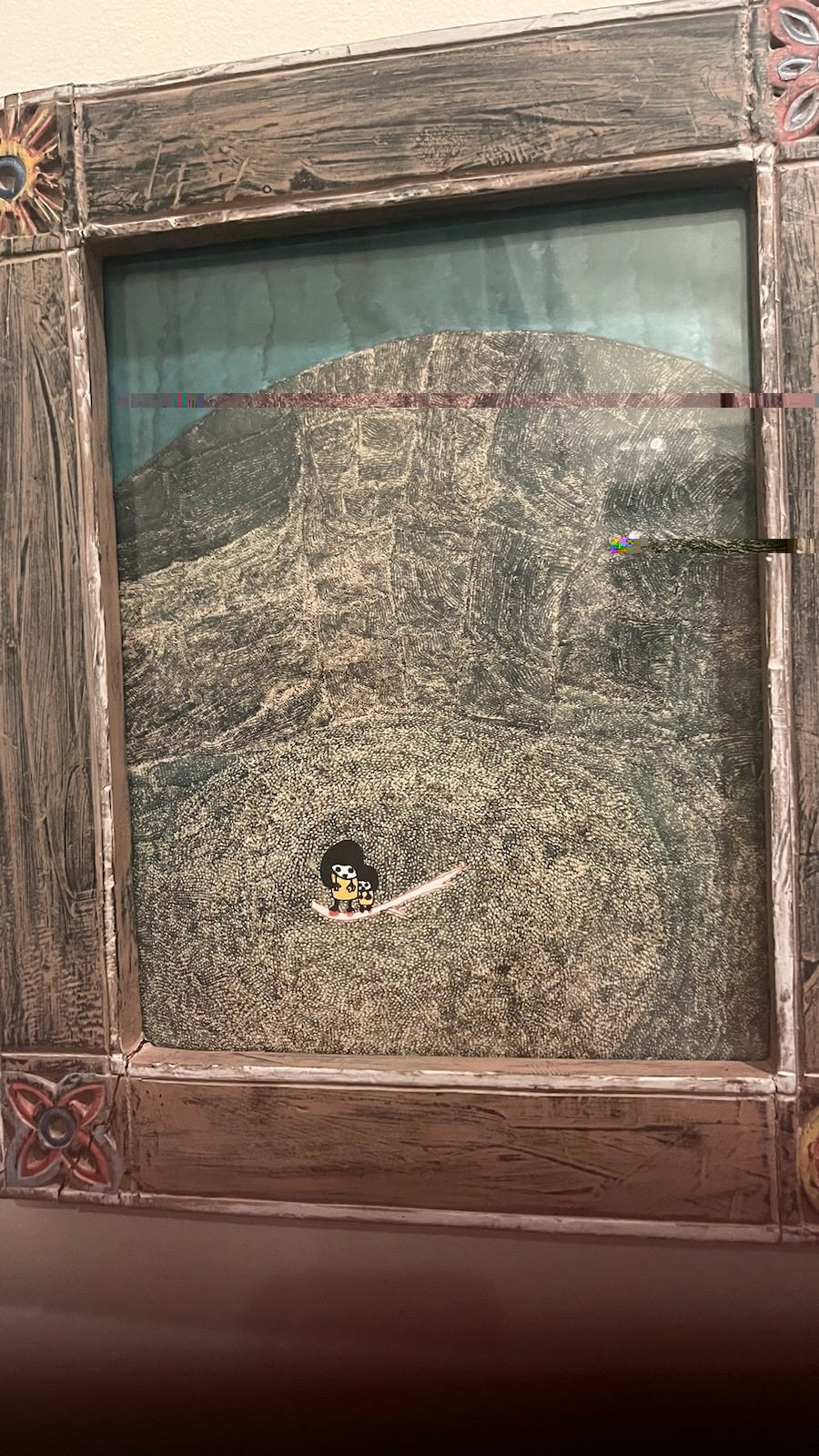

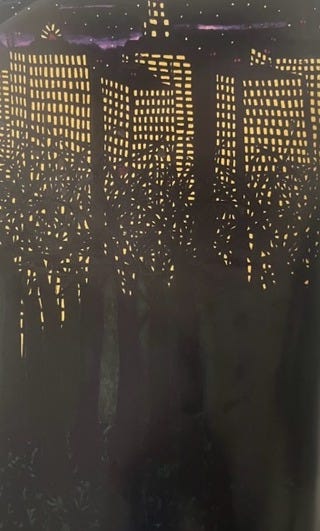

While I’ll leave the experts to talk about Murakami and Kusama and their ilk, I draw your attention to the below art done by Autistic Japanese children. These paintings and drawings are featured in one of my prized possession—an art catalog I found at the Argosy bookstore many years ago. The catalogue was from an exhibit at NYC’s Japan Society, which featured the work of Autistic Japanese children who lived at the Nemunoki school in Japan. Check out the insane attention to detail and perspective of being small in a big world that will surely move you. When I was younger and my main mode of decoration was cutting out images from magazines, I promptly cut out these pages, framed and hung them up. They clearly spoke to me (and I can’t recall whether I discovered this catalog before having my son who is Autistic). Even today, in my mature abode, I keep one framed image below and when people come over, they always stand before it and admire the art. Do you, like me, feel anything looking at these images?

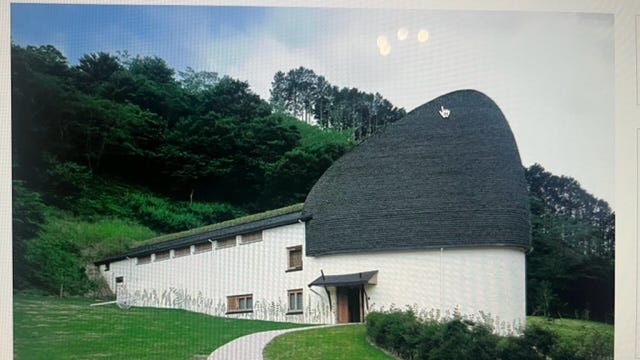

I recently shared this artwork with my therapist who has an Autistic daughter and she remarked that each piece has an Autistic perspective—the level of detail and the slightly off kilter perspective. But as one writer in the Nemunoki art catalog explained, the art is also distinctly Japanese. Apparently the kids’ art (that is apparently unguided/untaught by anyone) uses color directly with no overlapping or shading as is more common in Western art and includes an intricate level of detail and vertical perspective, that are hallmarks of Japanese art. So at least these Autistic children left to their own, contrary to stereotypes about Autistic children, are heavily influenced by their surrounding culture/environment. As my son is Autistic and proud, we may go to the Nemunoki art museum in Japan that contains the art of students that is housed in this cool looking building when we visit Japan hopefully next year.

Kiyomi Muramatsu, In the Green (age 10) (above)

Akihiro Ito, Manhattan Night (Age 18)

I am not alone in my appreciation of kooky, Japanese sub cultures. I just learned about a Japanese festival called Jimi (Mundane) Halloween, which delights me to no end. “Apparently, the tradition was started in 2014 by a group of adults at Daily Portal Z who “kind of wanted to participate in the festivities of Halloween, but were too embarrassed to go all out in witch or zombie costumes.” So instead of the flashy and flamboyant costumes they had been seeing gain popularity in Japan, they decided to dress up in mundane, everyday costumes.”

I leave you with some ideas for a Jimi Halloween costume that come from my own life: a woman on the Sweetgreens check out line who can’t figure out where to swipe her credit card on the reader and taps many spots (me sometimes), a woman who sometimes can’t remember if she discarded her contacts because sometimes they roll back into her eyes from overuse. (To do this costume I’d somehow dry out a slew of contact lenses and glue them together and somehow affix them to my face near my eyes?). Who is with me to try this out? Can you come up with more?

Xoxo CMCA

Thanks for reading Crazy Middle Class Asian!